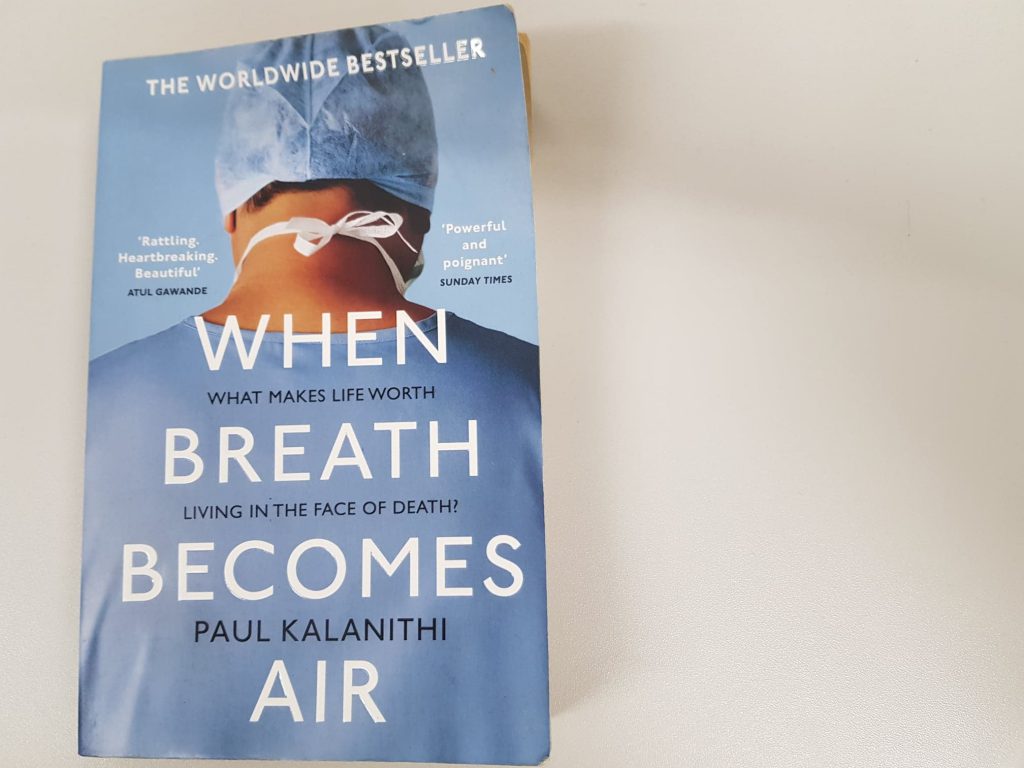

Paul Kalanithi’s ‘When Breath Becomes Air’: A Review

‘When Breath Becomes Air’ is a moving memoir written by thirty-six year old neurosurgeon, Paul Kalanithi, diagnosed with terminal lung cancer as he approaches the pinnacle of his career.

In the face of impending death, Kalanithi delves into the intersection of medicine, philosophy, religion, science and literature seemingly searching for an answer to the oft-repeated question, ‘what is the meaning of life?’

Kalanithi provides the reader with some clarity, eloquently articulating thoughts and emotions difficult to untangle in your own mind, let alone explain to others. Whilst doing so, he recalls anecdotes from his life before diagnosis, injecting effortless humour into his musings.

Abraham Verghese’s foreword urges the reader to listen to Kalanithi in the context of a capitalist society consumed by technology, meaningless communication and fleeting happiness. Verghese pleads, ‘In the silences between his words, listen to what you have to say back.’

Diagnosis

Kalanithi was on the cusp of what he perceived to be happiness, but his diagnosis changed everything.

My life had been building potential, potential that would now go unrealized. I had planned to do so much, and I had come so close. I was physically debilitated, my imagined future and my personal identity collapsed, and I faced the same existential quandries my patients faced. The lung cancer diagnosis was confirmed. My carefully planned and hard-won future no longer existed. Death, so familiar to me in my work, was now paying a personal visit.

Reflection

After his diagnosis, Kalanithi reflects on his motivation to become a doctor, ‘I had started in this career, in part, to pursue death: to grasp it, uncloak it, and see it eye-to-eye, unblinking…’ but he admits being so often in the presence of the death, instead made him almost blind to it.

He then goes on to question what makes a good doctor? A good person? He juxtaposes life and death; patient and doctor; clinical perfection and human error; arrogance and empathy; work and family; faith and reason.

Upon hearing the news that a friend from medical school had been hit by a car and died, Kalanithi considers his own human error. He admits to falling short with patient care at times of exhaustion and becoming desensitised to the reality of illness for his patients. The death of his own friend challenged his learned mindset in which illness, death and loss had become routine.

Expressing feelings of guilt, he states, ‘In that moment, all my occasions of failed empathy came rushing back to me… The people whose suffering I saw, noted, and neatly packaged into various diagnoses, the significance of which I failed to recognise…’ Understandably, his own diagnosis further intensifies these feelings.

Survivorship

He expresses the confusing paradox that many cancer patients feel: the gratitude for being alive and resentment for his significantly compromised life. He explains, ‘Verb conjugation became muddled. Which was correct? “I am a neurosurgeon,” “I was a neurosurgeon,” “I had been a neurosurgeon before and will be again”?’

Despite his diagnosis, Kalanithi and his wife (Lucy) have a baby girl. They name her Elizabeth Acadia “Cady” Kalanithi.

Yet there is dynamism in our house. Our daughter was born days after I was released from the hospital. Week to week, she blossoms: a first grasp, a first smile, a first laugh. Her pediatrician regularly records her growth on charts, tick marks of her progress over time. A brightening newness surrounds her. As she sits in my lap smiling, enthralled by my tuneless singing, an incandescence lights the room.

Epilogue

Poignantly, Kalanithi was unable to finish his memoir and Lucy completed it for him. She recalls her husband’s deteriorating condition and describes the way in which he held their baby shortly before taking his last breaths.

Kalanithi’s account of life and death will resonate with all readers but I think his words will hold particular resonance to those living with a terminal illness and the loved ones they will leave behind, as he depicts the familiar scenes of hospital visits, waiting room experiences and awkward, uncertain moments spent at home with family post-diagnosis.

Kalanithi recalls his younger self arguing that ‘happiness was not the point of life.’ Perhaps as he grew older and death loomed, he realised happiness was exactly the point of life.

Medstars Medical Concierge Service

Looking for extra guidance when it comes to your healthcare? Sometimes interpreting medical information and making the best decisions can be daunting and complicated. Our private medical concierge service provides easy access to top UK health experts. We guide our patients with genuine choice and trust, offering a bespoke service for anyone in the world seeking private UK healthcare. Learn more about Medstars Medical Concierge Service. Want to learn more about providing our medical concierge service as an employee benefit? Learn more about Medstars Medical Concierge for Business.